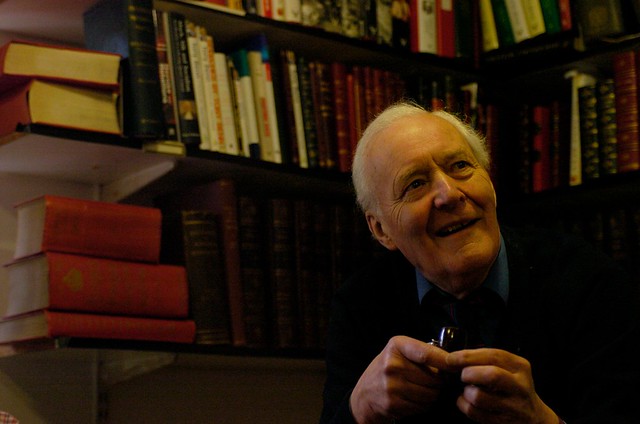

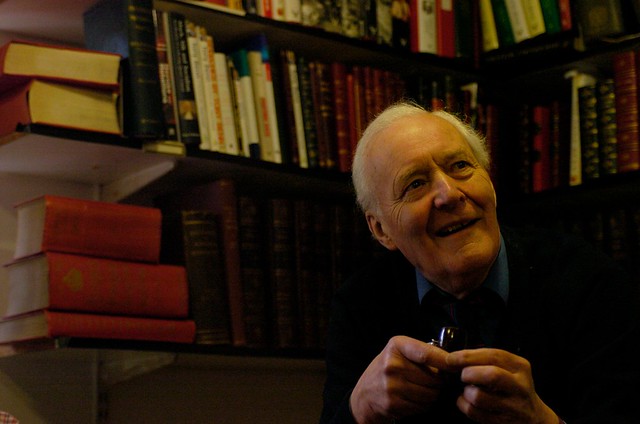

Following our review of ‘The Big Meeting’, Durham Magazine caught up with filmmaker John Irvin. Though he’s probably best known for his work on shows and films such as Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy and Mandela’s Gun, John’s first film was a short documentary about the Durham Miner’s Gala. We talked about his roots in the North East, his links with the Labour movement, and the early days of his film career.

The Big Meeting is screening in Cinemas nationwide.

Screening information can be found at https://www.galafilm.co.uk/

In the film my attention was drawn to one of the first films you made in your career, ‘Gala Day’. Watching the clips of that was very interesting because I couldn’t tell if the Gala was exactly the same or completely different back then. What was it like filming that?

I was at school in Durham and I definitely from the age of 13 or 14 I was witnessing the Gala during that period. After I left school i went to London to the London School of film technique. I was thinking about what, what to do, what kind of film to make and I got a job in newsreels. I was part of a group of young filmmakers so I suggested that the Gala would make a really great movie and the people I was talking to were from the south so they had no idea what I was talking about. I was talking about it and as I described it I became, you know, inspired. I I thought ‘one way or another I’m going to find a way to make this film’. So I wrote a about the day and submitted it to the British Experimental Film fund. And luckily, one of the adjudicators or one of the men on the committee (who was distributing the money) had been attended Durham University in his youth and he thought it was a terrific idea.

The other members of the committee were completely ignorant of the spectacle and the significance of the of the event but this guy thought it was a really wonderful idea. At the time I’d been working on and off freelancing, I was only 22 I think, as a camera assistant with the National Coal Board Film Unit because they had a weekly magazine. At the time their documentaries were about putting up a camera and filming what went on in front of it. My plan was to take four camera units into the gala and and join in the fun, to take the cameras into the action, which at the time was revolutionary by British documentary standards. Hand held cameras were still just a prospect and we had to adapt existing cameras. We all did it for nothing; a friends in the film school and a few friends I’ve made in the industry.

We took two full cars up the A1 and picked up some cameras, and we adapted them in the car with some Swiss sound equipment. We charged up the A1 and got out the cars, started filming, and filmed through the night. We went back on Sunday, and went back to work the following day. It took us a year to edit the film!

Luckily it was picked up and was shown at the London Film Festival and got very good reviews so the the BBC picked it up and showed it. And I’ve been saying “action” and “cut” ever since. But it got a bit tricky because Sam Watson who was a very distinguished leader of the mineworkers had gotten wind of my pitch and and my pitch to the BFI was obviously a little bit sensational. I described not just the speeches from the platform I referred to the fighting in the pubs and what some of the sons and daughters of the miners got up to behind their parents backs. I gave a rather lurid description which upset the miners very badly. But I was trying to raise money which required a bit of hyperbole and so I gave it to them.

I thought that would come up! I was doing some research about that after watching The Big Meeting and found that your film caused so much upset that it actually made it all the way to Parliament! Is that true?

I went up to see Sam Watson because I knew his daughter who I went to school with. At that time we were waging a war of words in the Daily Herald and the Northern Echo and I tried to explain to him what I thought of as a celebration. After all it was the only holiday that the mineworkers were traditionally allowed in the 19th century – it was the annual holiday. The whole point was letting rip and letting go so it seemed to be pretty natural. What was wrong with that?

When I asked to come and film again he said “why don’t you come and do it next year when all the noise from this has died down a little bit” but I said no, I want to do it this year so he said “well I cant guarantee your safety” so I was expecting a lynch mob, when in fact it was all very friendly. (laughing)

The Parliamentary Labour party wanted a screening when the film was finished and I was happy to show it to them. In the middle of the film Manny Shinwell started shouting and got up to storm out and as he stormed out Bessie Braddock got up and spat at it! The lights came up at the end of the screening and some of the younger Labour MPs got up and actually said that they loved it and that it was exactly what we needed.

Some of them were a bit offended but I said “well that’s okay”, I didn’t want to put anyone to sleep. What I wanted to do was show was the vitality and the sheer joy of being alive and the girls dancing down the street. ‘Kiss me quick’ hats and that sort of thing. To me it was a medieval fair, not that I’ve been to one, but judging by the pictures it was raucous and it was thrilling. I just wanted to share that experience with an audience. In film terms it was considered an important link between the free cinema movement and the television documentary. It provided a bridge between those two types of genre.

It sounds like the Gala left quite an impression on you. Which memories stick out the most?

I was about twelve years old when I went to my first Gala and I wasn’t supposed to go. That made it even more exciting because it was sort of forbidden territory, I wanted to sneak out and join the crowds. The music was the first thing that struck me. The first thing that makes your heart race is the brass bands gathering at the station. In those days there were eighty or ninety of them tuning up and marching down towards the bridge. It was beating against your chest – God! The drums and the brass marching through the street at the beginning of the day. Its all about solidarity, it was like a triumph! The miners marching in a glorious parade from the station right down to the racecourse all playing different tunes. It was a wonderful cacophony. It was a fabulous start before you got to all the exhortations. Its interesting about those, I remember George Brown on the platform saying “whether we go in or whether we go out…” and so on. It was ‘62 and he was talking about the European Union, so it was still a big issue then and it still hasn’t been resolved! As I say I was interested in reversing the techniques of the time, of sticking a tripod in the ground and then observing it. To me film making is all about joining the action.

Did you make any other films that related to the miners or the Gala?

I made a film in ‘66 I think, it was about the general strike. I went to Wheatley Hill and recreated what it was like during the general strike. This was for BBC north. I recreated what it was like for the village during that period. It always makes me laugh when people say that the BBC’s run by left wing luvvies and all that because the people I spoke to were actually extremely right wing and they actually banned the film. They put it out in the North only, on New Years eve when everyone was in the pub! I said “why are you doing this to me?”, the response was “well its a bit one-sided, isn’t it?” but I said “well how could it not be?” (laughter). He said “well where’s the point of view of the owners?” Well the owners would have to explain why their safety standards were, you know, negligible. The point of the film was to show what it was like for the miners. Anyway, the BBC thought it was far too one sided and far too left wing and therefore they didn’t show it. So when people say the BBC have a left wing bias I say “well its not as simple as that”. I was punished for it – I couldn’t get another job from them for another couple of years.

You seem to be very sympathetic to the plight of the miners, do you have family connections to mining?

I grew up in North Shields and my family connection was to Scottish fishermen who worked on trawlers (I always wanted to get on to a trawler to film, but it was considered too dangerous in those days). I have a great affinity and passionate sympathy for the miners, obviously. In fact the local Labour Party in Wheatley Hill wanted to secure a seat for me in Parliament. They said that they’d like me to represent them. I went back to London and thought about whether I wanted to continue being a film maker or go into politics. All of my friends at film school said “go into politics!” I think they thought it would be one less rival! But I stayed in the territory that I knew best.

What other work did you do in the Labour movement?

I was actually head of the documentary section of my local trade union and spoke every year at the TUC. I worked with Tony Benn. He asked if we would help with a party political broadcast and we did. I thought he was a good communicator. Later on I didn’t always agree with his policies but he was impressive; I think he sounded even more impressive. I thought certainly that in terms of the labour movement he was effective. He said to me in a screening room in SOHO, puffing on his pipe “so how do you think you can help us” and in the arrogance of youth I said to him “well I think I can help you win the next election”, he puffed on his pipe and said “we have a few ideas of our own you know!” (laughter)

Do you think being from the North East made it more difficult to get into your industry?

That’s a good question. I don’t think so. To the credit of the film industry, when I got into it it was very egalitarian, it didn’t matter where you came from. I think coming from the north east gave me a certain bonus, I’ll say that. I went to London and came back to the north a much happier bunny. I have a great rapport about the north east and I’m fiercely sentimental about it. The first time I ever had a Newcastle brown ale from a can I was in Sam Watson’s house. There was only one pub in London where you could get it. Being a Geordie in London at that time if you got into trouble you’d just have to tell people that and they would sort of back off. (laughter) There was certainly a fighting tradition, though I certainly didn’t look for fights.