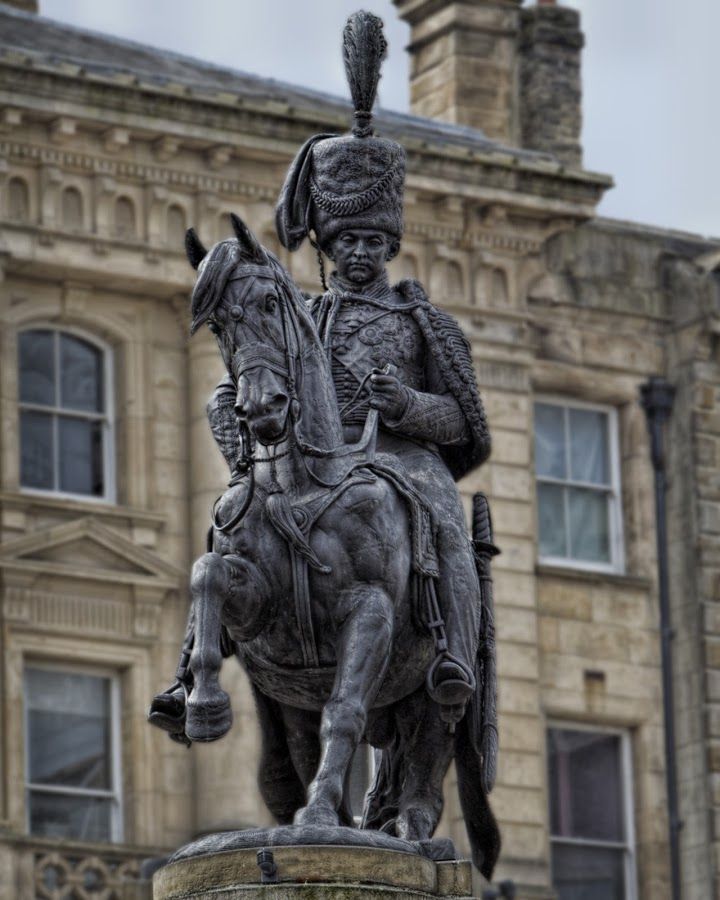

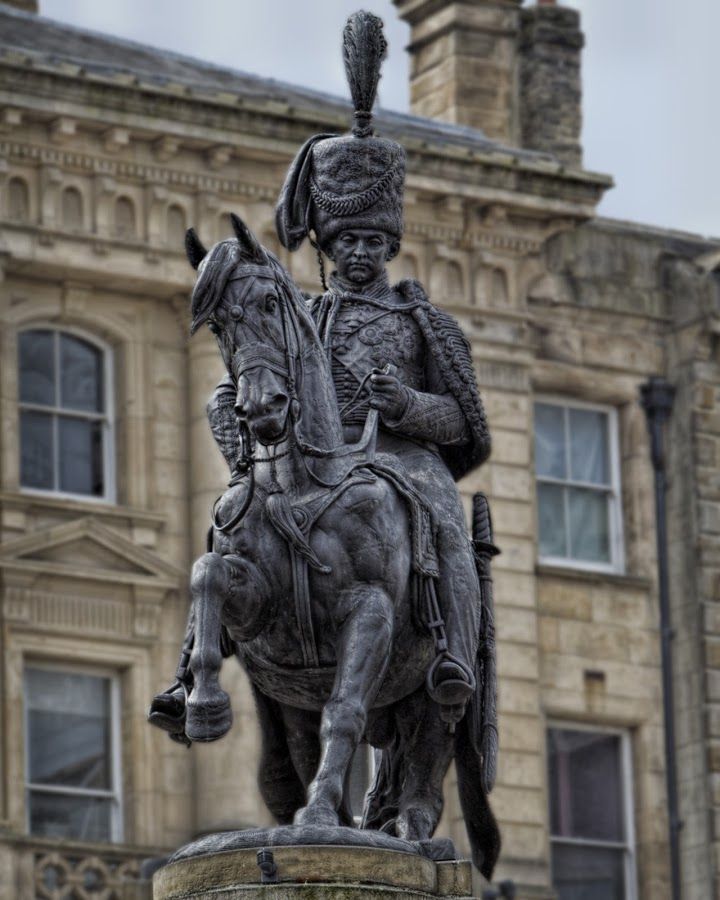

Probably the most prominent landmark in Durham Market Place is the huge, double life-sized statue of a military-looking gentleman on a horse.

Though he towers over the Market Place in all his martial pomp, many residents of County Durham don’t know who the statue represents, even some of those who use it as a convenient meeting point. The sculpture is often simply referred to as ‘the man on the horse’.

The statue, erected in 1861, is of Charles William Vane Stewart (1778-1854), the 3rd Marquis of Londonderry.

Charles William Vane Stewart certainly had a colourful life and career. A famous cavalryman, he led a brigade of Hussars and for a time served as the right-hand man of the Duke of Wellington, the hero of the Battle of Waterloo.

Following his retirement from the military, the Marquis of Londonderry did much to develop the Durham coalfields and railways, and created the County Durham port of Seaham Harbour.

But, in County Durham especially, the Marquis was a controversial and often unpopular figure. And his equestrian statue in Durham Market Place has always been somewhat controversial too, from even before it was put up until very recent times.

Here’s a tale of suicidal sculptors, bankrupt artists, irate tradesmen, lawsuits, angry miners, a worried council, attempts to ruin the town of Sunderland, and a bizarre modern uproar concerning the horse’s rear end.

The Controversial Creation, Problematic Setting up and ‘Traumatic’ Unveiling of Durham Market Place’s Statue of the 3rd Marquis of Londonderry

When the Marquis of Londonderry died in 1854, his widow set up a subscription committee to raise money for a statue of him. As the Marquis had many friends among the gentry, the scheme was a success, raising £2,000, a substantial amount of money at that time.

As so much cash had been collected, the plans for the statue became quite grand. The decision was made to seat the Marquis on a horse and make both man and horse double life-sized. And to create this huge equestrian statue, the Marquis’s wife would employ one of the nation’s most talented sculptors.

The artist commissioned was Raphael Monti (1818-1881), an English-based Italian sculptor from Milan. Monti would use a new, highly innovative technique to produce his image of the Marquis.

This technique involved placing an electroplated copper covering over a plaster base. Due to the copper being corroded over time, this covering has given the statue its greenish tinge. The Durham Market Place statue is believed to be the largest artwork ever produced using the electroplating method.

The statue shows the Marquis at the age of 42, resplendent in the uniform of a Hussar.

Monti’s magnificent sculpture, however, was soon causing problems. First of all, Monti went bankrupt just before the statue was due to be delivered. The artist’s creditors confiscated the statue and the Marquis of Londonderry’s widow had to shell out £1,000 to have the sculpture released.

Next, Durham Council became alarmed at the statue’s sheer size. The message somehow hadn’t got through to them that it was going to be a double life-sized monument.

In panic, feeling the statue would be oversized in the Market Place, the council tried to persuade Durham University to erect it on Palace Green. The university refused so the council reluctantly had to allow it to be set up in Durham Market Place.

Dismayed by this decision, five local tradesmen launched a lawsuit, claiming that the enormous monument would restrict movement in the Market Place and impoverish their businesses.

Their suit failed, however, and the statue was duly unveiled on 2nd December 1861, in a bombastic ceremony involving the rifle volunteers of Seaham, Sunderland and Durham City. Among those in attendance was the future prime minister, Benjamin Disraeli (1804-1881).

An interesting piece of Durham folklore is attached to the unveiling of the statue. It’s said that Raphael Monti was so proud of his sculpture that he challenged all those present to try to find fault with it, promising to reward anyone who could identify the tiniest mistake.

Many onlookers examined the equestrian statue, but all had to admit that the artwork was perfect. Then a blind man appeared and asked to be lifted up to inspect the piece.

After groping around the statue with his hands, the blind man declared there was indeed a fault – the horse had no tongue. It’s said that Monti was so devastated by this omission that he committed suicide.

Though this makes an intriguing story, it has little grounding in fact. The horse does indeed have a tongue and Raphael Monti didn’t commit suicide after the statue was revealed. The sculptor went on to create more works and lived until 1881.

Who Was Charles William Vane Stewart (the 3rd Marquis of Londonderry) and What Was His Connection to County Durham?

Charles William Stewart was born in Dublin in 1778, to a family with links to the monarchs of Scotland. Educated at Eaton, he entered the army at the age of just 12, becoming a major at 17.

Noted for his skill as a cavalryman, he led a Hussar brigade in 1808 and served as adjutant general to the Duke of Westminster from 1809. This job was, however – due to its overly administrative nature – not much to Stewart’s liking and the Duke of Westminster doesn’t seem to have held him in high regard, referring to him as ‘a sad brouillon and mischief maker’. Stewart resigned from the position in February 1812.

Stewart was involved in military campaigns in Spain, Portugal, Belgium and Holland and also worked as a diplomat during an age in which Napoleon’s conquests were causing large-scale ructions in Europe.

Charles William Stewart became a marquis following the suicide of his older half-brother Robert Stewart, who was Viscount Castlereagh and the 2nd Marquis of Londonderry (1769-1822). Castlereagh was a famous figure, having served as Foreign Secretary and Leader of the House of Commons, but he seems to have suffered a nervous breakdown due to overwork and, possibly, attempts to blackmail him over accusations of homosexuality.

Charles William Stewart, however, had no links to County Durham until he married Frances Anne Vane Tempest in 1819.

Anne was an heiress to estates in County Durham and Ireland and, upon his marriage, Stewart took on his wife’s name ‘Vane’ as part of his own. Among the County Durham estates Stewart acquired were Long Newton village (where he’s buried) and Wynyard Hall, both close to Stockton-on-Tees.

The Marquis spent £130,000 (equivalent to around £10.77 million today) building and furnishing a mansion at Wynyard Park. However, in 1841, when the mansion was almost complete, it was gutted by fire and had to be restored and remodelled.

Why Was the 3rd Marquis of Londonderry a Controversial Figure in County Durham?

After retiring from the military, Stewart became interested in developing County Durham’s coal industry. He invested a great deal of money in mines and railways, especially in the eastern parts of the county.

What the Marquis of Londonderry needed, however, was a way to transport the coal his mines produced. He first tried to do this by negotiating with the River Wear Commissioners in Sunderland, asking for exclusive rights to export coal via the Wear.

When the Commissioners refused him, the Marquis is alleged to have flown into a rage, promising he would make sure that Sunderland was ruined and that he would ‘see grass grow in the streets’ of the town.

Refused access to the Wear, the Marquis decided to develop a port of his own to compete with Sunderland. He established Seaham Harbour, completed in 1831, but – although this proved a profitable undertaking – it did little to dent Sunderland’s prosperity.

Interestingly, Durham Market Place’s other historic statue, that of the Roman sea god Neptune, also references an unsuccessful attempt to exploit the trading potential of the River Wear. The statue was given to Durham in 1729 to symbolise a scheme to make Durham into a seaport by improving navigation on the river.

Despite his support for Durham’s coal industry, the Marquis of Londonderry was unpopular with local miners. A committed Tory, who served as an MP, he opposed legislation that would have humanised work practices in the nation’s collieries.

The Marquis was against trade unions and broke strikes in his pits by bringing in Cornish tin miners. During the strikes, he sent letters to Seaham merchants, threatening to evict any traders who supplied striking miners with goods.

He refused to allow his collieries to be inspected and – as many boys laboured in his mines – opposed attempts to increase the school leaving age to 12.

The Marquis was also criticised for his response to the Irish Potato Famine (1845-9). Though one of Britain’s richest men, with large landholdings in Ireland, he and his wife gave only £30 towards famine relief while spending £150,000 (around £13.3 million today) on renovating their Irish mansion Mount Stewart.

By the time of the Marquis of Londonderry’s death, his estates were bringing in £75,000 per year, three-quarters of which was estimated to be generated by coalmining.

It’s perhaps an irony that a left-leaning city like Durham, with strong trade union connections, has a massive statue to an anti-union Tory mine owner in its Market Place.

The Later History of Durham Market Place’s Equestrian Statue – a View from the Rear?

Despite the controversy surrounding the statue of Charles William Vane Stewart, it has remained in Durham Market Place ever since its erection in 1861. It has always been a well-known meeting place, especially for courting couples.

In the year 1951, however, the statue was removed as it had to undergo important repairs. When the statue returned in 1952, a second plaque was placed on its plinth, which was unveiled by the 8th Marquis of Londonderry.

The statue was also renovated in 2009-10, after which it was moved 16 metres south of its original position in Durham Market Place.

The council wished to do this to open up the Market Place to make it a more suitable space for events and performances. Some locals, however, complained this would mean that – on entering the Market Place from Silver Street – they would be confronted with the sight of the horse’s rear end.

The managing director of Durham Markets, Colin Wilkes, stated, “For 150 years, people approaching the Market Place from Claypath have had to look at the back of the horse. In future, it can be the turn of people approaching from Silver Street.”

“Whichever way it is positioned, we cannot get away from the fact that it does have a rear end.”

Harvey Dowdy, the director of Durham City Vision, which organised the relocation, said, “We believe the statue will be more prominent facing across the Market Place and down Claypath from the top of Silver Street.”

“Unfortunately, whichever way it is facing, the horse’s rear will face the opposite direction. Our studies have shown that more people approach the Market Place from Claypath than they do from the direction of Silver Street.”

The equestrian statue of the 3rd Marquis of Londonderry – though a striking feature of Durham Market Place – has certainly proved controversial down the ages and it will be interesting to see if the monument generates any more disputes in the future.

David Castleton writes about the darker and quirkier sides of history, folklore and literature at his blog The Serpent’s Pen.

(This article’s main image – showing Durham Market Place’s equestrian statue – is courtesy of My Boys Club.)