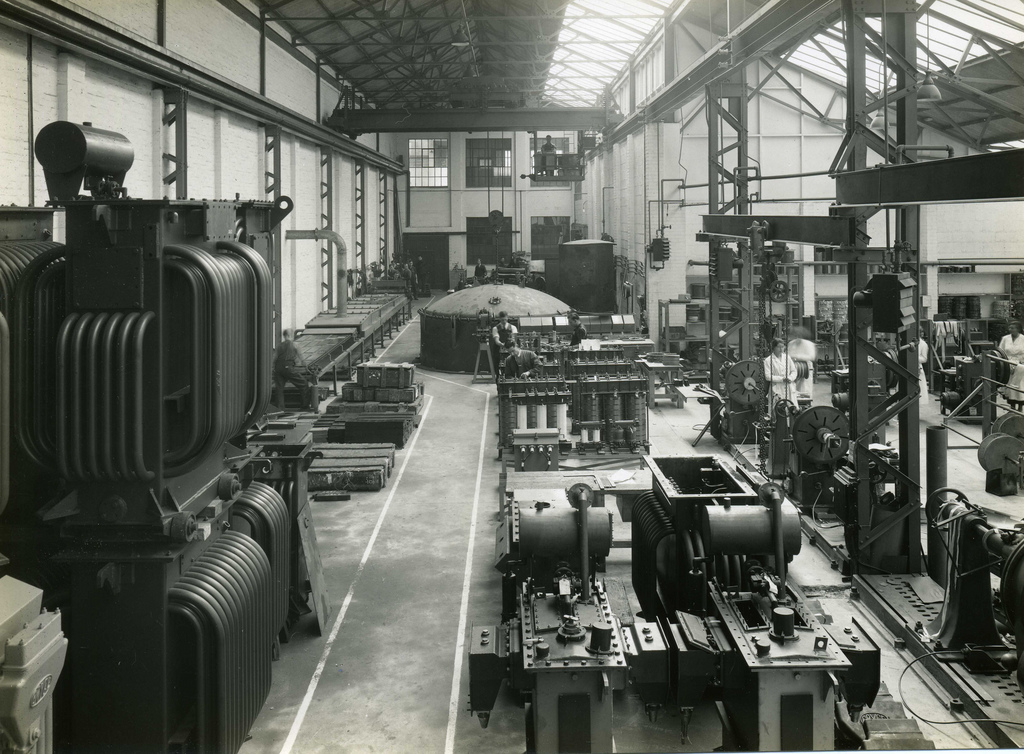

A Durham University academic has uncovered an enormous surveillance campaign by the British government directed at industrial workers suspected of being communists.

Research by Dr Jennifer Luff has found that the campaign, which ran from the 1920s to the 1940s, monitored workers employed in government-owned dockyards, munitions factories and other industrial sites.

Though communism was not illegal at the time, thousands of workers were subject to surveillance techniques such as mail interception and tailing. As a result, many of these workers were sacked or denied jobs, and many found it difficult to gain subsequent employment.

Dr Luff drew her findings from secret government documents that have now been released to the UK National Archives.

Dr Luff, an associate professor of American history at Durham University, said, “The scale of the surveillance programme undertaken by the British government was truly remarkable. At one point, MI5 were checking over 25,000 names a month yet the British public knew nothing about this.”

“Workers were monitored and blacklisted from government employment without the opportunity to see or challenge the evidence presented against them.”

The programme, which led to some convictions for spying and treason, was kept secret and its existence was repeatedly denied by government ministers, including prime minister Stanley Baldwin.

Research by Jennifer Luff @durham_history reveals British government’s history of secret anti-communist surveillance https://t.co/mBemZHmjBU pic.twitter.com/RarFxsA8XU

— Durham University (@durham_uni) June 15, 2017

Documents show that workers were often monitored for the most trivial of reasons and that, in some cases, the surveillance went on for decades before the targets were found to be innocent.

The employees of some private firms that had government military contracts were also monitored, as were workers in the Post Office.

The programme was not, however, applied to the upper reaches of the civil service. This meant that double agents like Donald Mclean and Guy Burgess – who were members of the notorious ‘Cambridge Five’ spy ring – were not placed under investigation.

Dr Jennifer Luff said, “After the General Strike in June 1926, there was deep concern within the War Office and MI5 that communists could infiltrate Britain’s ‘war machine’.”

“The cabinet took a secret decision that active communists should be discharged without pension, and workers who merely subscribed to communist beliefs should be removed through attrition.”

“Because this policy was never announced publicly, those affected would never know why they lost their jobs or were unable to gain future employment.”

Dr Luff found that some government officials criticised the policy on the grounds that communism was not illegal, that workers didn’t have the chance to leave the communist movement in order to keep their jobs, and that the programme placed a strain on government resources.

Dr Luff said, “Until now Britain has been viewed as moderate and held up in contrast to the more open political oppression, such as McCarthyism (an anti-communist campaign directed at people in the US government, military and entertainment industry), that took place in the USA.”

“However, these findings show that Britain was waging its own anti-communist political fight.”

“Understanding our histories helps inform current debate, and clearly there is a need to better understand what has, until now, been an entirely unknown aspect of British political history.”

(Featured image courtesy of born1945, from Flickr Creative Commons)